Preview the first chapter of my book, The Humorist: Adventures in Adulting & Horror Movies, shared in full below.

The first movie that ever scared me was a 1980s creature feature called Ghoulies.

My mom rented it for my brother, Chris, and me one roaring Friday night from our local Blockbuster Video. Back then, this was our idea of a party. We’d hit Blockbuster and troll the aisles, the heels of our sneakers exploding red with every step, and we’d search for the night’s main event. It was the ‘90s, and we were explorers in there, flying blind and taking chances. We’d barrel through the sections — New Releases to Favorites to Comedy to Action — without a single internet review or Rotten Tomatoes score to lead our way. The risk was part of the ritual. The thrill of the hunt. The high stakes. We bet it all on every movie we ever rented from that place, and we couldn’t get enough. We craved its rush.

We were eight-year-old gamblers and ten-year-old ramblers, holding the fate of our nights in our hands with every tape. We had only one guiding light: VHS cover art, and we lived and died young by it.

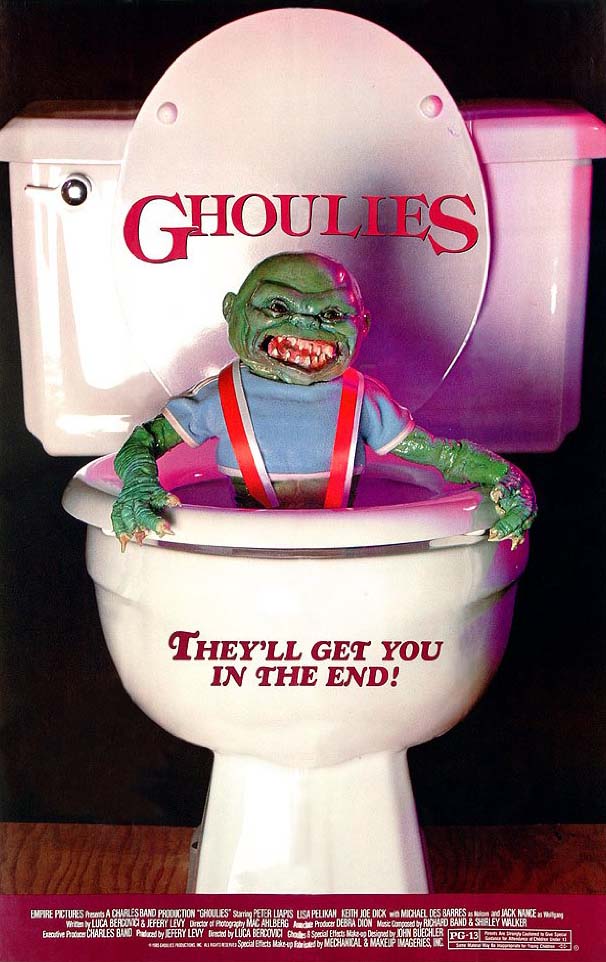

Finally, we hit the Horror section. That’s where we found Ghoulies — and its cover art was primo.

In it, a green monster-baby wearing red suspenders — think an angry-looking Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle, with wrinkly arms and sharp fingernails — was holding himself, waist up, from out of a toilet bowl.

Tagline: “They’ll get you in the end!”

Say no more, Ghoulies. You’re coming with us.

“MOM!” I probably yelled, coming in hot to establish the seriousness of this request. “Can we get this? We have to get this!”

“Eh, I dunno,” she said. “Looks kinda scary.”

Clearly she was hysterical.

“We won’t get scared!” I whined.

“No way!” Chris jumped in.

“I’m not a baby anymore!”

“MOM!”

It’s easy to miss, but in this moment, we had seamlessly transitioned into the full-proof childhood negotiation technique known as “Shock-and-Awe.” It was sure to reinforce the gravity of the situation and overwhelm my mother into bending to our will.

We hit her with a surround-sound attack: me on one side, Chris on the other, raining pleads upon her like two verbal Gatlin guns, spraying and praying. It worked like a charm.

Before we knew it, we were in the checkout line, begging for Blockbuster’s signature $9 packs of Sour Punch and $52 buckets of popcorn.

“There’s popcorn at home,” my mom said, not even dignifying our request by looking down at our needy faces.

She was “Stonewalling” — a classic adult negotiation strategy, and one we knew well. We’d seen it employed many times before. We’d tried all of our tactics on her in the past in this line, such as:

- The Soft Sell (“Sure would be nice to get some of these M&Ms — and oh, wow, look: They’re only $8!);

- Reverse Psychology (“Hey, Chris, imagine if mom punished us by forcing us to eat a whole pack of these $11 Milk Duds!”);

- The Wet Ask (crying);

- and when desperate, we appealed to her maternal instincts, clutched our stomachs and writhed in fake pain: “But I’m staaaarving!” (This was known as The Hail Mary Plea, AKA The Self-Destruct Protocol. High risk, high reward.).

None of them worked.

My mom was good, real good. She never entered the snack line without an airtight exit strategy. In case of emergency, she always had a fail-safe “Would you rather go home with nothing?” she’d snarl, eyebrows raised, so smug. She knew she had us.

In that rope-lined maze, surrounded by sugar-coated temptations, my mother was the suburban version of a hardened war general. She never lost a battle. Not one.

Chris and I exchanged shrugs, almost impressed.

Game respect game.

“The tape is due back Wednesday,” the high school kid behind the counter — by my estimation at the time, roughly forty-three years old — mumbled. “And please rewind.”

I don’t blame my mother for the carnage that was about to ensue. How could she have known that when she grabbed that VHS copy from the shelf that what she was really buying was a lifetime of trauma for her youngest son? After all, we’d seen wacky monster movies before — your Gremlins and Little Monsters. Why would Ghoulies be any different?

NOW PLAYING

— GHOULIES (1985) —

Takeaway: Begin with the “end” in mind.

At home, we popped in the VHS, heard the sweet sound of gears pull the tape inside the VCR, the mechanical hum of wheels spinning film over rollers, transforming our darkened living room into a grand theater: rippled red velvet walls, balcony suites. And me and Chris had the best seats in the house.

We fast-forwarded through the coming attractions then pressed Play.

Black screen. Men in cloaks. One of them, the leader, had shimmering green eyes and long devil horns. He was ranting and raving, some kind of ceremony.

Me and Chris were immediately rapt. I pulled the blanket over my knees and up to my chin.

The horned leader was handed something wrapped inside of a black shall. We see that it’s a baby.

The leader set it on an alter, chanted incantations, his voice deep and echoing, growing into a scream.

The baby starts to cry.

I look at Chris. He doesn’t look at me, his eyes locked onto the screen.

The leader grabs a dagger, looks down at the baby. More chanting.

From the kitchen, I hear my dad say something like, “What’s that they’re watching?”

The horned leader raises the knife, his green eyes flashing with ‘80s neon: a telltale sign of unadulterated evil.

Light flares from the knife’s pointed edge. The newborn squeals.

This is where, in my memory, all hell breaks loose.

I screech. My brother gasps.

My mom runs in and blocks the TV with her body, frantically pushing buttons on the VCR, hunting for the one that reads “Eject.”

“Don’t look!” she screams, utilizing the age-old parenting technique known as “Misdirected Anger.”

I spill the popcorn.

The tape slides out. I pull the blanket from over my eyes.

We made it all of five minutes in.

From the kitchen, my dad says something like, “I can go for some nice chicken soup.”

To this day, I’ve never seen the rest of Ghoulies.

Five minutes – that’s all it took of Ghoulies to scar me. It was my gateway into horror, the first spark of feeling what it’s like to be afraid of something vicariously — to experience real fear but from a safe distance, in the living room of the house I grew up in, with my parents close by, keeping watch.

This is where I first learned to observe from the periphery, and it kickstarted a lifelong obsession with horror cinema — with learning about the world and growing up through the prism of pop culture. Scary movies weave themselves into our genes, they persist because, no matter how old we get, we never outgrow fear. It’s the one constant throughline in each of our coming-of-age stories. It’s a drug, and I’ve been chasing its high — that suspenders-wearing, toilet bowl-living, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle-looking dragon — for as long as I can remember.

NOW PLAYING

— NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) —

Takeaway: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try to save for counseling — but your child is probably already damaged forever. You only get one shot at this.

In Night of the Living Dead, our protagonist is strong, assertive, logical. He does almost everything right. Yet, he still gets killed, unceremoniously, right before the credits roll — because he made one single mistake.

If that doesn’t tell you everything you need to know about parenting, I don’t know what does.

The Perils of Family Movie Night; or, E.T. the Extra-Traumatizing

My wife, Rebecca, and I started Family Movie Night as a way to spend more quality time with Charlotte. She was turning eight, and I’d been in her life since she was three. That first meeting, she was supposed to be sleeping but scampered out of her big-girl bed and into the living room of Rebecca’s then-apartment, holding princess figurines.

“Jasmine,” she grumbled from behind a pacifier, fully extending her arm to show me the toy.

“Oh, wow,” I said. “What a pretty dre—“

“Aurora!” she blurted out, not caring even a little about what I had to say and pushing a second toy toward my face.

These would prove to be the first of, oh, say 49,000 or so times since that she would interrupt me to offer podcast-worthy deep dives into her toy collection.

She ran away, bare feet clapping tile. Then she returned with more.

“Elsa!” she said, pinching the toy’s plastic dress to demonstrate how it can be removed and replaced with others.

“Cool! Is Elsa your fav—“

She was gone, running back to her room again to get more princesses.

It went on like this for the next fifteen minutes. Two years later, I’d give her a heart necklace and ask her to be my stepdaughter. She said yes.

“You know every wedding needs a flower girl,” I told her, the night that I proposed. “Think you’d want to be—“

She cut in, eyes locked onto the heart’s reds and pinks, and said, “I can’t stop looking at how sparkly it is!”

That time, I didn’t mind the interruption.

Ever since that day — call me a worrywart — I’ve made a concerted effort to not screw her up permanently. That’s been the goal. After all, what did I know about parenting? I was coming into this late and totally untrained. I was like a White House janitor stopping in the middle of cleaning the Oval Office to sneak a quick test drive in the president’s chair. First, I was reticent, making sure the coast was clear before listening to the seat sigh as I set my weight down onto it. Then, as I fingered the stitching on the leather armrests, I got more used to the idea. I picked up a pen, motioned it toward imaginary world leaders gathered around me and said, “I believe we should … not … go to war,” and they all nodded heartily in agreement, having never thought of it that way before.

Yep, I thought, pressing Add to Cart on a World’s Greatest Dad mug I was buying for myself online. I could totally do this job.

Meanwhile, Rebecca had already done the hard work: the late nights, the potty training. She’d made it through that newborn period where the baby’s head, like something from a sci-fi space horror, has an undeveloped soft spot (AKA “the accidental kill switch”). And she did it all as a single parent.

Rebecca was the first responder, the hero with dirty hands and a blood, sweat and tears-stained record of valor. I was just mop-up, the cleaning crew, support staff. My goal from here: Do no harm — and overall, I’d say I was succeeding.

That is, until we launched Family Movie Night.

Generally, the films I curated for this weekly event weren’t risqué. We started with the soft stuff — your Disneys and Pixars. Then, we segued into a ‘90s kids-movie marathon: the titles from my youth. We watched stuff like The Sandlot, The Goonies and Mrs. Doubtfire, the latter of which I was surprised to realize is actually a deeply sad exploration of divorce, on top of being a zany, fun and sometimes problematic romp about Robin Williams dressing in drag and carrying out drive-by fruitings on his ex-wife’s new boyfriend.

Charlotte was loving it. She was ready for horror.

NOW PLAYING

— CASPER (1995) —

Takeaway: Introduce your child to death ASAP. Make sure they understand that everyone they love will die. Begin this process immediately, then reinforce first thing in the morning (ideally bedside, just as they open their eyes) every day until they are eighteen years old and no longer your problem.

“How about Casper the friendly ghost? I offered, flipping through Netflix.

“What’s it about?” she asked, carefully picking the peppers off her slice of pizza like a world-class surgeon with ace-level steady-hand. “Dab my brow,” I imagined her telling her assistants. “Pepperoni — stat!”

“Um, it’s about a ghost named Casper, but he’s frien—“

“Okay!”

And we were off to the races.

Casper is surprisingly depressing, too, with adult themes about death and coping throughout, and I noticed this is a real trend with kids’ movies from “back in my day.” They were fun and funny, but they also never shied away from darkness[1].

Next was The Addams Family, and Charlotte lapped it right up. None of the ghosts or ghouls in Beetlejuice phased her, either.

I was shocked, convinced it was a sign that kids today were desensitized.

“It’s the iPads!” I ranted to Rebecca, channeling my inner old man yelling at the clouds. “YouTube. Social media. Their modern sensibilities are hardened!”

And then we watched E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Dear God, did we ever watch E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

NOW PLAYING

— E.T. THE EXTRA TERRESTRIAL (1982) —

Takeaway: Don’t get attached. Love is pain.

But wait — E.T. isn’t even horror, you’re probably thinking. Wrong!

Listen, I was cocky, too. When my wife asked if E.T. was okay to show Char, I went full Hell’s Kitchen bookie, taking bets on a fight I knew was fixed.

“Becky, baby” I says to her, I says. “It’s a classic. We can’t lose!”

I scoffed, shook my head. Poor Rebecca. She wasn’t exposed to a lot of pop culture as a kid and was seeing a lot of these movies for the first time, along with Charlotte. But this was far from my first rodeo. I knew better.

“You kiddin’?” I chortled, scooping Charlotte’s peppers from her plate and dumping them onto my last slice. “Sweethaht, it’s Spielboig!”

Remember those moments I mentioned earlier, the ones you can’t get back as parents — the one mistake the hero makes from Night of the Living Dead? This was mine.

E.T. had been on Earth too long, and he was growing weak. The bicycles that flew past the moon? That magic was long gone, bucko. Now, he was a chalky, pale mess, more gray than brown. The light in his eyes, and in his finger, had dulled. He was too far from home, and his body was shutting down.

Worse, he had formed such a bond with Elliot, the cherub-faced little boy, no older than 8, that Elliot was experiencing the same agony as his best friend, E.T.

“I think we’re dying,” Elliot squeaked to his mother in the movie, his voice creaky and small, and Rebecca shot me one of those wide-eyed glances that parents exchange over their kids heads to communicate dismay (and/or marital regret).

Then scientists arrive dressed as astronauts, and in this moment, E.T. becomes a full-blown home-invasion flick.

The spacemen push their way through the doors and windows of the family’s house. They establish a perimeter, quarantine the place. Emergency lights flash.

Next, E.T. and Elliot are strapped to steel tables beside one another. The scientists huff inside their suits like Darth Vader. The camera goes from steady to shaky handhelds. You can hardly make out any words with so many doctors in the room, all talking over one another, checking the alien’s vitals, poking and prodding.

Elliot screams for E.T., reaching out both arms. Then E.T. goes limp.

The doctors rush to intubate. They press on his chest, compressions to restart his heart. Over and over, they press. Nothing works.

They grab the shock paddles.

“One, two, three — clear!” they say, pumping electricity through E.T.’s lifeless body. It jolts violently.

They do it again. And again.

“One, two, three — clear!”

Charlotte turns to me in this moment, sad-eyed.

“Why did you make us watch this?” Her voice is just as creaky and small as Elliot’s.

That’s when I knew this was her Ghoulies moment, that pivotal event that’ll imprint an alien-shaped trauma on her subconscious, one she’ll find a million different ways to bury, just as I have, as she gets older.

“Don’t worry,” I said, shifting in my seat. “He’ll come back.”

But it was too late. Charlotte was balled up beside Rebecca now, nuzzling into her shoulder.

The doctors onscreen stopped with the paddles. They sighed.

“He’s gone,” one of them said.

Funny, I thought. E.T. died at the exact same moment as Charlotte’s innocence. But hey, bright side: At least the damage is only permanent, right?

[FOOTNOTES]

[1] How else could you explain a movie like My Girl, a go-to for my sweet Grandma Nancy, who used to pop it in for my brother and me all the time as kids, in between emptying pans of homemade meatballs into pots of her famous Sunday gravy.

Note: My Girl is not a horror movie, but it is a movie that murders Macaulay Culkin — America’s favorite child, here playing a fragile, allergy-ridden little boy — by attacking him with a swarm of killer bees. At his funeral — open casket, of course — his best friend in the movie, the titular “girl,” Vada, insists on putting Macaulay’s glasses on his corpse.

“He can’t see without his glasses!” she weeps.

“He’s gone, honey,” her father, inexplicably played by Dan Akroyd, tells her while bracing her shoulders. “He’s gone.”

And Akroyd should know: After all, he’s a mortician who works from home — because who needs the commute, right? So, the family’s basement is a morgue, full of dead bodies, and wouldn’t you know it, one day Vada gets locked down there. And she panics. She pounds on the door, pleading for help, but nobody hears. Finally, she collapses into a ball on the top steps, pressing her hands against her ears and cry-singing: “Here she comes just-a walking down the street, singing doo-ah-diddie-diddie-dum-diddie-doo.”

The kid is tortured, and back at Macaulay’s funeral, for reasons I’ll never understand, her father’s tough-love approach doesn’t do the trick.

“He was gonna be an acrobat!” Vada moans. Then she runs away. (Akroyd stops chasing after her about three feet past their doorway. This is a guy who does not care for travel.)

For any child of the ‘90s, My Girl was traumatizing. But remember — not a horror movie.

Share your thoughts below, and sign up for my mailing list to be notified of future chapter teasers, book updates, news and promotions!

One response to “An Introduction to Horror Cinema: Parental Discretion is Advised”

As usual, your writing had me laughing out loud and brought me right back to those Blockbuster days…where it all began…

LikeLike